Search

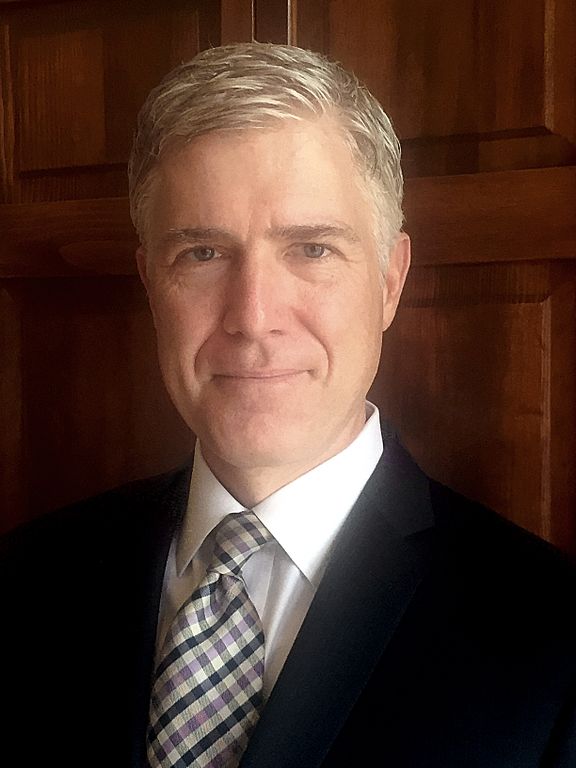

I wonder how Trump’s nominee, Neil Gorsuch, might decide a SCOTUS leave-accommodation ADA case.

I hear many of you are dying for my hot take on how Tenth Circuit Judge Neil M. Gorsuch may shape employment law as a member of the U.S. Supreme Court. Then again, those could be the voices in my head.

I hear many of you are dying for my hot take on how Tenth Circuit Judge Neil M. Gorsuch may shape employment law as a member of the U.S. Supreme Court. Then again, those could be the voices in my head.

***Q-tips***

Ah, that’s better. Where was I? Oh yes, happy Groundhog Day.

Well, I’ll tell you this. Don’t push your luck with Judge Gorsuch on leave as an ADA accommodation.

After the nomination became official on Tuesday night, I did a little research.

As I was flipping through Judge Gorsuch’s employment-law opinions, I found this one involving a former Kansas State professor and reasonable accommodations under the Rehabilitation Act (think: public-sector version of this Americans with Disabilities Act). Indeed, I remembered blogging his decision in Hwang v. Kansas State University. It was this post entitled, “Just how badly did a federal appellate court trash extended leave as a reasonable accommodation?“

The answer is “very.” To borrow a line from Steve Austin — no, not the Six Million Dollar Man; rather, the greatest Steve Austin that ever lived, Stone Cold Steve Austin — Judge Gorsuch stomped a mud hole and walked it dry.

Sure, Judge Gorsuch did acknowledge that a “brief absence” from work could allow the employee to perform the essential functions of the job. “After all,” he noted. “[F]ew jobs require an employee to be on watch 24 hours a day, 7 days a week without the occasional sick day.”

But, longer than that?!? Judge Gorsuch lamented that “it’s difficult to conceive how an employee’s absence for six months — an absence in which she could not work from home, part-time, or in any way in any place — could be consistent with discharging the essential functions of most any job in the national economy today.” (hyperlink added)

And how about inflexible leave policies? Remember when I told you they were bad? Yeah, well…

Judge Gorsuch opined that “an inflexible leave policy can serve to protect rather than threaten the rights of the disabled — by ensuring disabled employees’ leave requests aren’t secretly singled out for discriminatory treatment, as can happen in a leave system with fewer rules, more discretion, and less transparency.”

(Let’s face it. While, I attended law school at “the Harvard of the Mid-Atlantic” a/k/a The George Washington University Law School, Judge Gorsuch attended the actual Harvard Law School. So, while I do have a blog, I should probably be carrying his bag and picking up his judicial robe from the dry cleaners. Who ya gonna trust?)

Plus, you may have read that Judge Gorsuch isn’t too big on deferring to a government agency’s interpretation of the law. Yep, we got some of that here too, as he blasted the EEOC’s guidance on modifying leave policies:

[T]he EEOC manual commands our deference only to the extent its reasoning actually proves persuasive. And the sentence Ms. Hwang cites doesn’t seek to persuade us of much. It indicates that an employer “must” modify a leave policy if the employee “needs” a modification to ensure a “reasonable accommodation”— that is, unless two listed conditions are met. But none of this answers the antecedent question we face in this case: When is a modification to an inflexible leave policy legally necessary to provide a reasonable accommodation?

In sum, I pity the fool with the first ADA case by before Justice Gorsuch.

What’s my prediction?

The Employer Handbook Blog

The Employer Handbook Blog